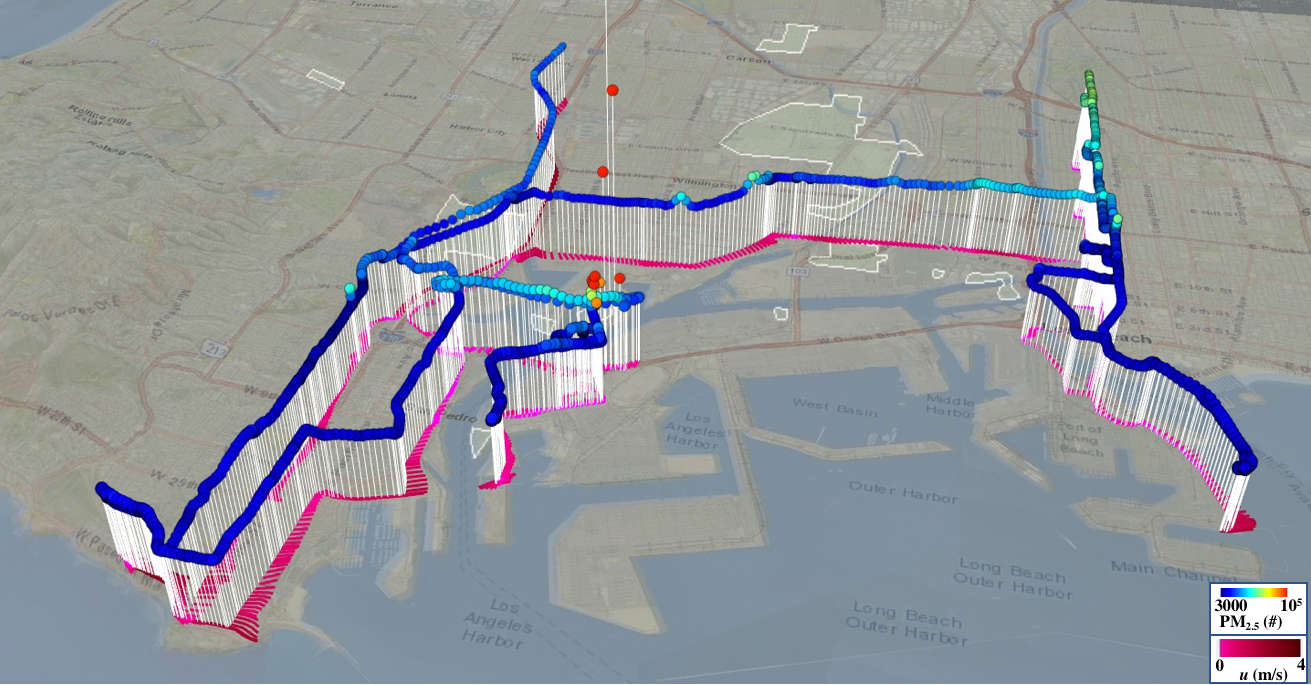

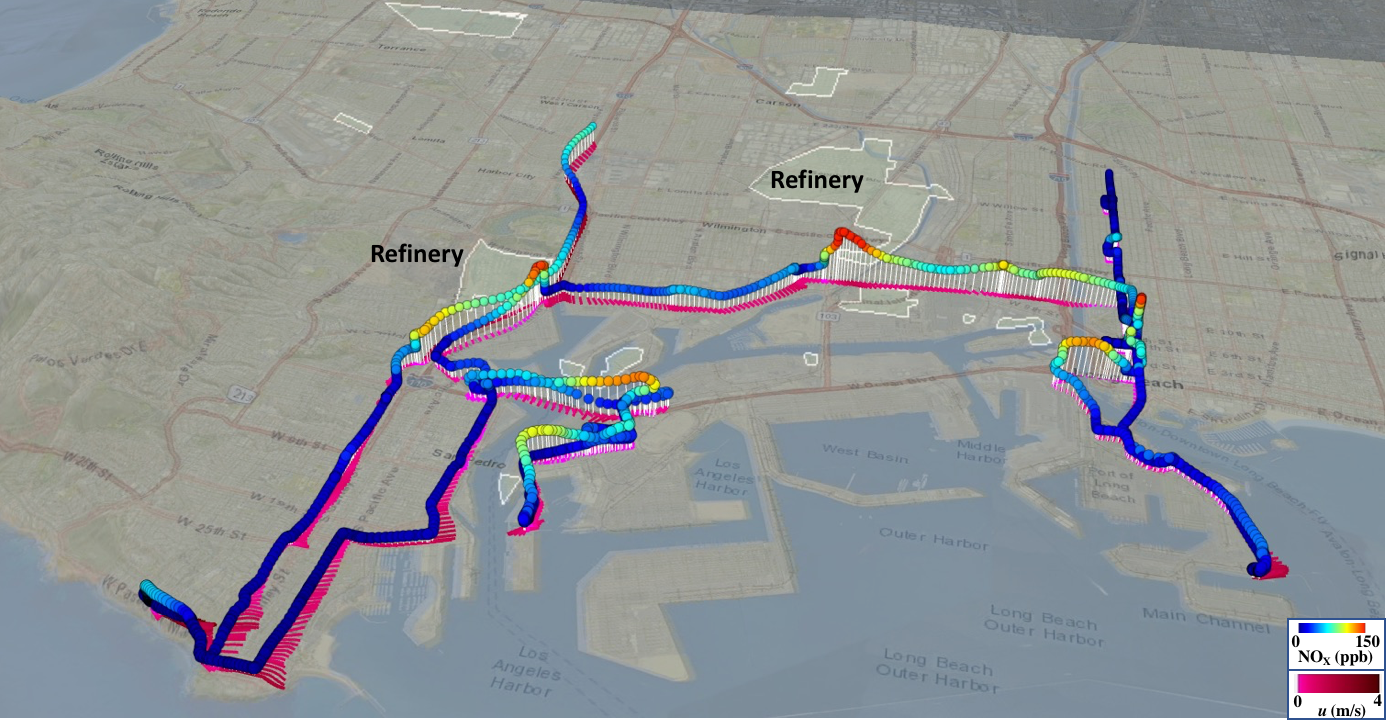

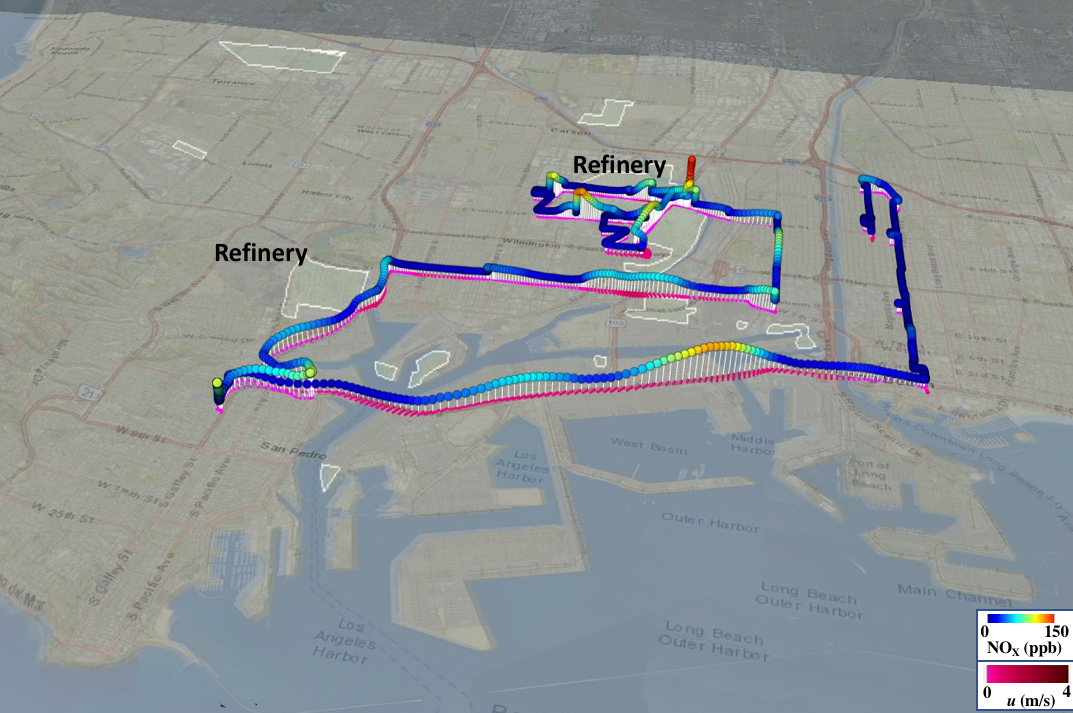

After the stay-at-home order was implemented, BRI conducted several air quality surveys of the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles (hereafter referred to as “the Ports”) and surrounding area which found impressively low levels of air pollutants commonly associated with activity at the Ports. The stay-at-home order and subsequent slowing down of business, traffic, and activity at the Ports had driven a dramatic decrease in pollutant concentrations. For example, NOX was 300 ppb in the summer of 2019, but was 30 ppb in May 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 shutdown. Ports’ area pollutants arise from a number of sources: heavy-duty diesel trucks, idling freighters, and the major traffic artery, the I-710 freeway, where trucks and other business traffic head in and out of the Ports. Elevated levels were measured of pollutants including NOX, particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide SO2, as well as other trace gases.

Idling freighters waiting offshore the Ports to the southeast on 2 Nov. 2020. Photo by Ira Leifer.

The Long Beach communities to the east and northeast of the Ports are subject both to pollution from the Ports and emissions from area refineries, which release pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and a vast range of trace gases. Surveys investigated the difference in atmospheric chemistry for the northern Long Beach neighborhoods compared to the neighborhoods of southern Long Beach. The north is expected to receive emissions from both the I-710, refineries, and the Ports, whereas the south Long Beach neighborhoods are expected to receive emissions from the I-710 and the Ports but not the refineries. This implies that the CoVid shutdowns should have provided greater relief to the southern communities of Long Beach.

Aerial view of the Port of Long Beach.

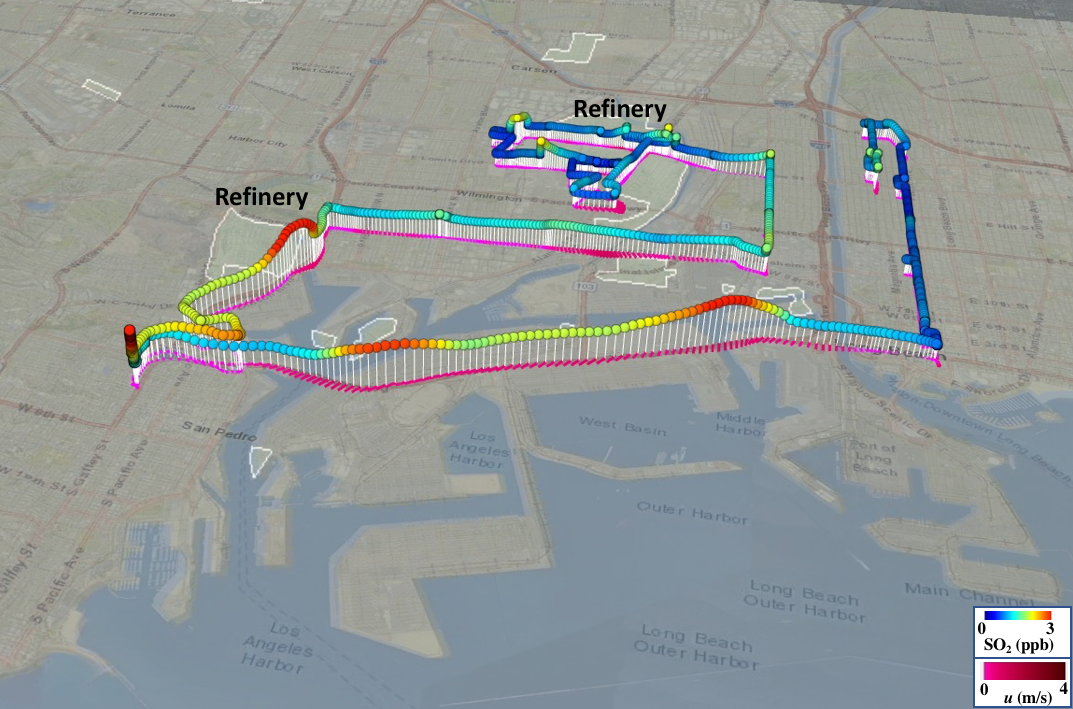

By September (six months into the pandemic), Port activity had returned to normal or even rose to elevated levels – at one point the Ports were so busy that shipping containers had to be stored offsite. BRI returned to the Port at the beginning of November to survey the air now that normal activity had resumed. This survey also filled in gaps in the previous field trip particularly with respect to background (Pacific) air sampling (samples collected at the south bluffs of nearby San Pedro) as well as sampling at the Japanese Fishing Memorial and the Cosco terminal near the Queen Mary. Data were collected by SISTER™, BRI’s newest mobile air quality laboratory. No signature of offshore vessels was observed during the survey, and based on the observed location of idling freighters, their emissions are likely to flow onshore to the southeast of the Ports under prevailing daytime winds. The air quality survey generally found that typical air pollution gas concentrations had recovered to elevated levels. NOx was found to be 150 ppb which is standard for this time of year and represents a significant increase as compared to the 30 ppb observed in May, during the shutdown.

Hybrid tugboat, the Carolyn Dorothy, at the Port of Long Beach.

Motivating these surveys is a need for better understanding of the health implications of planned air pollution improvements at the Ports from electrification. These health effects differ depending on which pollutants are present and their concentrations. Diesel vehicles (like the trucks which transport shipping containers to and from the Ports) produce more NOx than regular gasoline powered cars. These emissions react with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from either traffic or industry to form ozone, which impacts respiratory health (Knowlton et al., 2004). The Ports, area refineries, and diesel trucking release aerosols or particulate matter (PM) with major health concerns. PM affects mainly the respiratory and cardiovascular systems (Kim, Kabir & Kabir, 2015), but has also been studied for its associations with diabetes prevalence (Pearson et al., 2010). Overall air pollution contributed to over 2 million deaths per year globally and between 2.1 and 0.47 million of these deaths are attributed to PM (Shah et al., 2013; Chuang et al., 2011).

The COVID-19 crisis provided BRI a golden opportunity to collect preview data on the effects of expected pollution decreases from the Ports due to planned electrification. Due to other area pollution sources, it is possible that expected health benefits may be less than anticipated, and merits detailed studies.

Data from the survey below:

© 2021 Bubbleology Research International. All rights reserved.